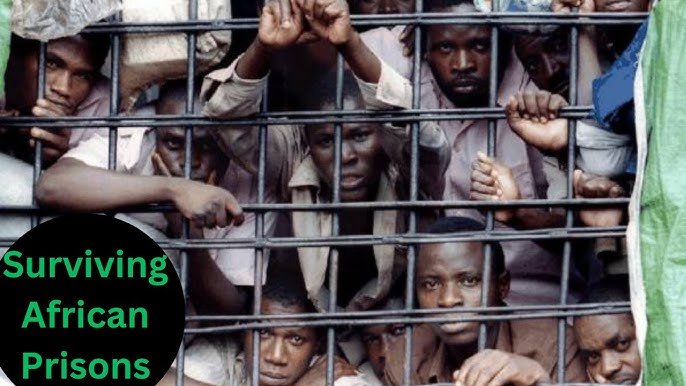

Nigeria’s prison population is more than 76,000, housed in 240 correctional centres. About 70% of these inmates are still awaiting trial. They have been arrested and charged, but not yet convicted or cleared.

This is the highest percentage of awaiting-trial prisoners in Africa. World Prison Brief’s latest report puts the figure at 12.4% for Ghana and 32.9% for South Africa.

The presumption of innocence is enshrined in Nigeria’s constitution, in section 36(5). It says:

Every person who is charged with a criminal offence shall be presumed to be innocent until he is proved guilty.

But the reality in Nigeria, as a number of researchers have shown, is that many people accused of crimes are presumed to be guilty. They are arrested and imprisoned before their cases are investigated.

Add to this a court system beset by delays and backlogs – it’s no wonder that Nigeria has so many inmates awaiting trial.

There are reports of accused people spending 10 years awaiting trial in the US, and between 12 and 15 years in Nigeria. This long wait in Nigeria is against section 296 of the 2015 Administration of Criminal Justice Act. The law provides that the period of remand should not exceed 28 days.

There have been some efforts to address the situation. The government offers some free legal services through the Legal Aid Council. It provides free legal assistance and representation, legal advice and alternative dispute resolution to indigent Nigerians to enhance access to justice. But the problem seems intractable.

Read more: Waiting for trial can be worse than facing the sentence: a study in Nigerian prisons

We wondered whether a technological solution might be a step towards addressing trial backlogs.

So we set out to study the situation at two correctional centres in Abakaliki and Afikpo, towns in Ebonyi State in south-east Nigeria. We investigated the underlying causes of long awaiting-trial periods and ways of addressing them.

The main causes of delay include the slow pace of investigation by the police and the loss of case files. Others are an inadequate court system and poor access to lawyers.

Our findings suggest that a repository portal system could help address most of the issues delaying trials. The portal would be a database where information about accused persons and their current trial status would be stored. It would be easily accessible, too. Material relating to investigations and police findings could be uploaded to the portal, which would then automatically allocate cases, depending on the nature of the alleged offences, to the relevant court.

This would address the challenge of loss or manipulation of data by criminal justice agents, like the police and correctional centre officials. It also tackles the challenge posed by manually sorting through large files.

A system like this has not been proposed or applied in any African country yet.